Author: Emese Szabó.

In the Transylvanian Hungarian theatrical culture, in which I was socialized, the tradition of repertory theatre is strong. When we look at the programs of theatres, we see texts from great classics and renowned contemporary playwrights. Experimental forms are rarely accessible to the audience. Coming from this background, Jasna Žmak’s performance was refreshing for me.

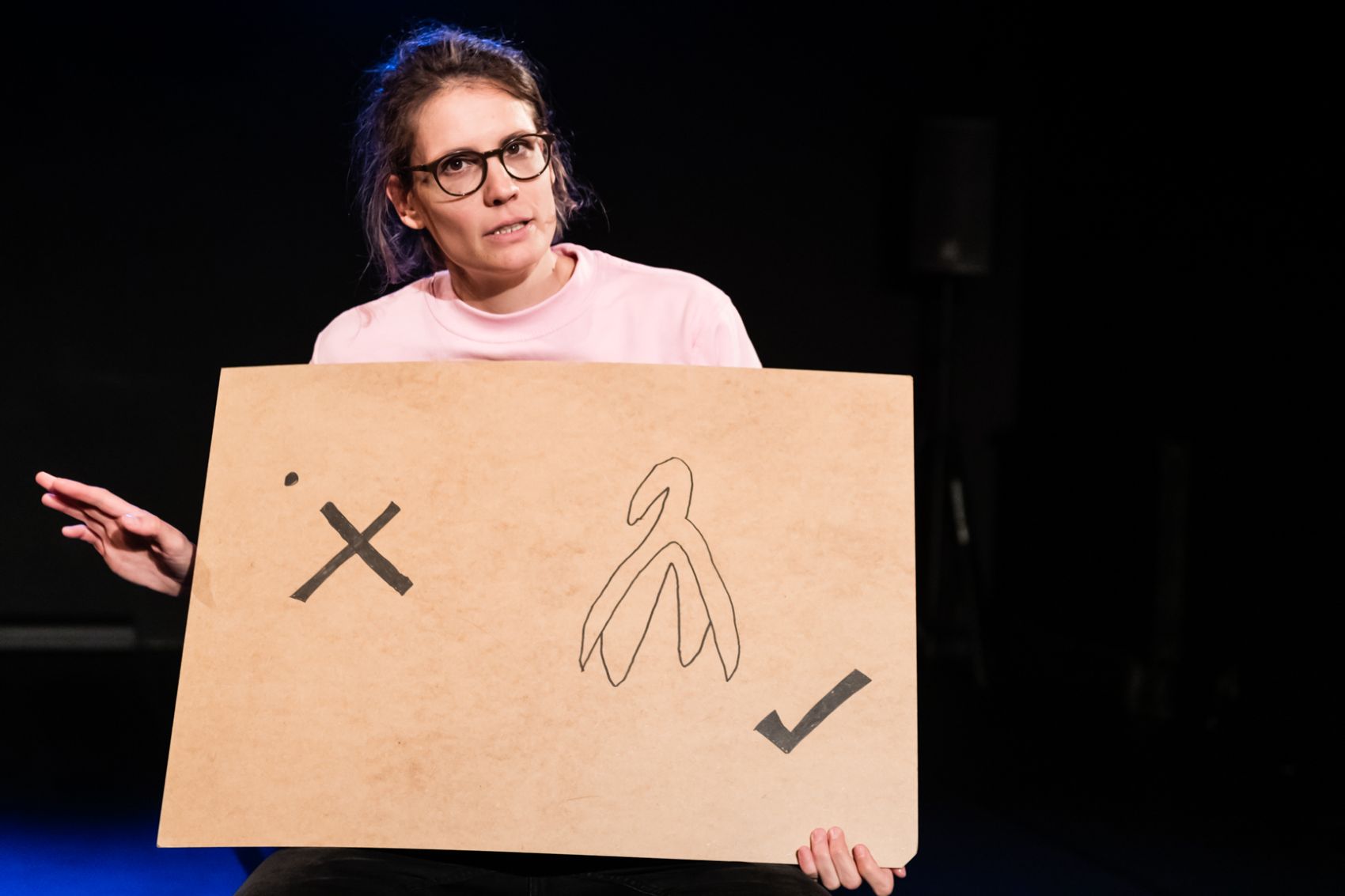

This is my truth, tell me yours by Jasna Žmak. Photo by Marcandrea.

This is my truth, tell me yours is a solo performance by dramaturg Jasna Žmak. Jasna has been suffering from tinnitus and hyperacusis since 2011. In the performance MandićMachine, directed by Bojan Jablanovec and performed by Marko Mandić, also a solo piece, Mandić selected someone from the audience and asked them to shoot him with a stage gun. On one occasion, Jasna was the one chosen. Since then, she has suffered from constant ringing in her ears.

The title of the performance foreshadows the directness that Žmak applies on stage. It also encapsulates the idea that this personal story extends beyond her individual experience, seeking to explore whether we, too, have experienced similar, unintended abuses.

Žmak begins to examine the entire context of her tinnitus and highlights that what happened to her was not a random accident but the result of an irresponsible decision. The shot, then, becomes the starting point, the pretext for the broader themes the performance addresses: patriarchy, responsibility in art, sexism, male and female masturbation, pleasure, and these topics’ fields of influence.

There are few set elements on stage – just a chair, a blanket, and a lamp – serving to evoke the referenced performance. This minimalist form reinforces the intimacy, keeping our attention on the performer. In the beginning, Žmak discusses how uncomfortable she is with performing, how she would rather hide from us, indicating that she is not doing the performance for pleasure but out of responsibility. On stage, she demonstrates the power of art – how it can cause lifelong harm if used improperly.

In terms of genre, the performance leans more toward a lecture-performance or stand-up routine, which suits the performer, who is primarily a dramaturg. The form is direct, narrative, and there is no traditional role-playing, meaning there is no distance between the audience and the actor; we become almost equal conversation partners. While everything that happens in the theatre raises the question of what is real and what is false – something Žmak herself touches on – in this case, the weight of the performance lies in our belief and knowledge that this is a true story. In the audience discussion, Žmak revealed she often gets the question whether this is even theater. I think questioning its theatricality is a narrow interpretation of theater’s boundaries. Its theatricality is also validated by the fact that it has received professional awards.

This is my truth, tell me yours by Jasna Žmak. Photo by Marcandrea.

At one point in the performance, Žmak reads from her e-mails, where the most frequently mentioned words are tinnitus and patriarchy. But how are these two connected? In the referenced performance, the male actor seemingly gives the audience member a power, a gesture that at first glance suggests that the actor can be shot, destroyed. But in reality, it is an illusion, as the pistol is not real, and the gesture is permissive: “I allow you, in my space, on my stage, to pretend to shoot me.” Perhaps the actor thought this was an exciting boundary-pushing moment, and the chosen audience member may have felt honored to be part of it. After all, Mandić is a respected, acclaimed actor – who would dare say no to him in such a situation?

I do not know the original context though, I can only interpret the gesture through Žmak’s understanding, and based on my own similar theatrical experiences, I find the situation familiar. It raises the question of whether we are capable of saying no in such a situation. This is not an equal relationship; the audience is subordinate to the performance since the actor has established the rules of the game.

Žmak shows that tinnitus is a constant, unavoidable noise that prevents silence, and patriarchy has a similarly unavoidable effect on our daily lives. These “noises” are not individual problems but are part of societal systems.

Although Marko Mandić’s name is mentioned several times, I do not think he is the target of revenge, anger, or blame. Jasna also mentioned that she spoke to other women who were invited to play the same role as she was, but for the others, it didn’t mean anything special, and it didn’t cause tinnitus or any lasting experience. In the narrative, Mandić embodies the patriarchal system, allowing us to examine issues such as male representation on stage through him. One of Žmak’s few props is a drawing of a clitoris, highlighting its actual size and how little we know about female pleasure. In contrast, Mandić frequently appears naked or half-naked in his roles, often mimicking masturbation, existing only for his own pleasure. The portrayal of female masturbation on stage – which is very much a representation of societal norms – is stigmatized, taboo, or designed to serve the male gaze. With this humorous depiction of the clitoris, Žmak draws attention to female pleasure and questions how we can liberate the female body in art, how we can portray female desire, pleasure, and sexuality on its own terms, free from the male gaze.

This is my truth, tell me yours by Jasna Žmak. Photo by Marcandrea.

I’ve told several people about this performance, and they asked if Jasna filed a report or if there were any legal consequences for this negligent act. From what we learn in the performance, it seems that she didn’t. What’s more – she says it jokingly, but it’s a fact – this performance is supported by the same institution that also supports Marko Mandić. This performance itself acts as a form of accountability. Through it, Žmak encourages us to move beyond our individual grievances and address the larger issue. For me, it also conveys that the artist has a responsibility to wield their power with care, while the audience has the task to recognize abuses and intervene or speak out, whether it’s about themselves or their fellow audience members.

This text was written by Emese Szabó within the framework of the Beyond Front@: Bridging Periphery project.